Life After Dolly: Ian Wilmut

Sixteen years after creating Dolly the sheep, the world's first cloned mammal, Professor Sir Ian Wilmut talks to Tom Ireland about the project that defined his career and how embryology and cell programming have advanced since then.

The Biologist Vol 59(4) p28-30

You initially studied agriculture. What led you to your career as an embryologist?

There is nothing in my background that would suggest I'd go into academic research. I worked on a farm and studied agriculture. Then on the last vacation of my degree I worked as an intern at the laboratory of Chris Polge, where we looked at pregnancy in livestock. It involved searching for and assessing embryos.My eight weeks there convinced me that embryology was what I wanted to do and I went on to do a PhD. I was working on embryo transfer in livestock and pre-natal mortality. That was my first area of interest – the variation in physiology and environmental factors that influence an embryo's survival.

I was then persuaded in the mid-80s that my embryo skills would be useful in trying to introduce additional genes into sheep so they would produce human proteins that could help fight disease. That led to the production of Tracy the sheep, who would have been the most famous sheep were it not for Dolly, as Tracy was producing human proteins in her milk.

Where has your research taken you since Dolly?

After Dolly's birth we did try what Shinya Yamanaka's team did in Kyoto [reprogramme adult cells to create stem cells, rather than creating embryos through 'cloning']. But we weren't successful. It was so exciting hearing what he had done because it meant you could do so much with cells – from creating pluripotent cells and changing cells from one lineage to another. What we are doing now is really an international collaboration. We grow specific cell types that are affected in inherited disease and can't be biopsied easily, like neural tissues. The differences between healthy and affected cells can be studied to establish therapies that prevent the development or progression of the disease.At the moment we're taking accessible cells from someone with inherited motor neurone disease and growing glia and motor neurones in the lab – we can then compare them with cells created from healthy individuals. It appears that, although symptoms start in the motor neurone, the glia may 'fan the flames' and exacerbate the disease.

What other types of tissue could you create?

Naively, I'd say almost everything. We have a project to produce cardiovascular cells with a view to looking at inherited conditions too.

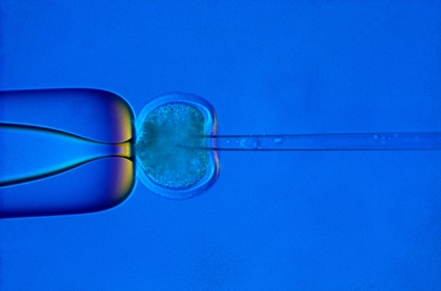

Nuclear transfer

Nuclear transfer

Could this technology eventually help grow entire disease-free organs?

Producing cells and small amounts of tissue is realistic; whole tissues and organs is more demanding. The idea of going in this direction as a treatment for inherited disease is that there are no pluripotent cells introduced into the patient and therefore no risk of introducing teratomas [tumours resulting from the abnormal development of stem cells].

Do you enjoy being widely known as the man behind Dolly the sheep?

Research like that requires people with lots of different skills – like micro-manipulation – and a huge background of staff working with the animals. It is truly a team effort. But I'm pleased to be recognised for it.

Does it affect your research to this day?

There is no question it has created opportunities for me, both socially and in my research. I was made director of the MRC Centre for Regenerative Medicine at the University of Edinburgh, which is quite extraordinary for someone with my background. The balance of positive and negative benefits has definitely been in my favour.

Did you ever worry about the controversy such projects would attract?

Some years earlier there had been lots of anti-vivisection activity in that part of Scotland, and in fact the [Roslin] Institute had been firebombed. We were perhaps fortunate in that if we had made our announcement about Dolly during that period it may have been worse. There were one or two protests but they were just fairly quiet ones outside the university gates.

Did you have any idea the work would produce such an impact?

No we didn't. Soon after the announcement I was woken up by a journalist calling from Moscow who told me that he, another journalist and a photographer would not just be coming over but spending a few days with us. For several days we were swamped.

Do you think the press and the general public understood what you were doing?

People did understand our motivations but didn't take much notice – the focus was, of course, on the possibilities of human cloning. As with these things, the sub- editors like to create headlines that attract people's interest and that's something you just have to accept. To their great credit, the Institute and the company that sponsored the research had arranged for us to have media training, which was incredibly useful.

What sort of scenarios worry you when you think about scientists changing human genomes, or cloning?

The first thing you have to imagine is correcting a mutation in a major dominant gene. The frightening thing is someone having the following conversation: "Son, we did this to try and do this, but..." That would just be awful.

There are alternatives to help couples select children without a certain condition, such as preimplantation genetic selection, of course. But even then, such is the nature of probability that some couples will not have any embryos that do not contain the gene for that condition.My own view has not changed on whether we should do reproductive cloning – couples who cannot have children should not be able to clone the father, for example. The social and psychological effects of being a clone would be too great. Perhaps they could be managed, but the clone of the father would not have the independence of a normal human. The pressure to be like their father would be so unusual.

How seriously do you take the threat of unlicensed cloning of humans by rogue scientists?

Well there are no cloned primates yet and we know that there are major biological differences between primates and humans. It's not going to be possible with the layers of regulation in this country and it would be very difficult to do illicitly because of the sort of work and technology required. But of course, the procedure is not illegal in all countries.

How many years are we from gene therapy being a mainstream treatment for inherited disease instead of an experimental one?

In terms of changing somatic cells, I think people must be very excited now and I don't think we are far from it being used to treat disease. Changing the fate of prospective children is different and something I have real anxiety about.

Do you think the UK's current system for debating ethics and regulating bioscience works and is fit for purpose?

In the UK, I think we should be very proud of the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority. It works very well and provides really good guidance.

Professor Sir Ian Wilmut is director of the Medical Research Council Centre for Regenerative Medicine at the University of Edinburgh. In 1996 his team at Edinburgh's Roslin Institute created Dolly the sheep, the first mammal to be cloned from an adult somatic cell.