Spotlight on: Parasitology

The Biologist Vol 61(4) p32-33

Parasitology is the study of the interaction between parasites and their hosts. In general, parasitologists tend to concentrate on eukaryotic parasites, such as lice, mites, protozoa and worms, with prokaryotic parasites and other infectious agents the focusof fields such as bacteriology, microbiology and virology. Parasites are extremely common, and are responsible for some of the world's most deadly illnesses, from dysentery and diarrhoea to malaria.

Why is it important?

It's estimated that at least half of all known species are parasitic, so understanding the life cycle and interaction of these organisms with their hosts is often key to understanding the dynamics of ecosystems generally. Parasites cause millions of deaths and billions of infections in humans every year, but parasites of crops and animals can have equally devastating effects by disrupting global food supplies and people's livelihoods.

Parasites are hugely diverse. From the well-known cuckoo, which hides its eggs in another bird's brood, to the horrific parasitic crustacean Cymothoa exigua, which destroys the tongues of fish and attaches itself where the tongue once was, the strategies parasites employ to exploit their hosts are often remarkable. Over a hundred species of fungi alone have evolved to manipulate the behaviour of ants, including one that causes the 'zombiefied' ant to climb a tree, die and release spores onto its fellow workers below. There are even parasites of these ant parasites, known as hyperparasites.

What careers are available?

Parasitologists are largely employed by public health bodies and research organisations to evaluate treatments, prophylactics and vaccines that prevent parasitic infections. Biotech companies and the pharmaceutical industry need parasitologists to help treat parasitic disease in humans, to prevent losses in agriculture and aquaculture, and to keep people's pets free from worms and fleas.

Just like bacteria, parasites can develop drug resistance, so understanding their genes, proteins, life cycle and evolution through research is also important in controlling infections and predicting future outbreaks. Many parasitologists will work in or visit developing countries, and there are also opportunities in charity and policy roles because of the field's links to international development.

How do I get into it?

Many parasitologists progress into research careers after specialising at master's or PhD level. The majority of parasitology courses are at postgraduate level; common courses include medical parasitology, molecular parasitology and vector biology. A few institutions, such as the University of Glasgow, offer parasitology degrees.

Where can I get more information?

The British Society for Parasitology represents the UK community of parasite researchers.

www.bsp.uk.net

At a glance

Name: Emily Adams

Name: Emily Adams

Profession: Lecturer in tropical diagnostics, Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine and University of Warwick (joint appointment)

Qualifications: BSc, MSc biosciences, PhD in molecular parasitology

Interests: Evaluation and implementation of diagnostics, and kinetoplastid diseases

What does your job involve?

I develop new tests to detect parasites, train people how to perform new diagnostic tests and to see how effective these are compared with more traditional procedures. I am involved in the development of simplified molecular tools to sensitively test for Kinetoplastida diseases such as leishmaniasis and trypanosomiasis.

So you don't just look down a microscope for these parasites any more then?

No. Microscopy has saved many lives and has been an excellent diagnostic tool, but you need skilled operators and it is easy to miss a low number of parasites. Molecular tests can give more accurate and rapid results. Most of them involve detecting the parasite's DNA in the blood.

How are these diseases spread?

They are both protozoa, spread by flies. Leishmania is spread via sandfly bites and causes a spectrum of illnesses and up to 50,000 deaths a year. Trypanosomiasis, or sleeping sickness, is caused by trypanosomes delivered in tsetse fly bites.

What does your typical day involve?

I'll usually have a Skype conversation with a project coordinator abroad and check how the enrolment of patients and results are going. Then I'll work on writing up a project for publication or peer reviewing other manuscripts. I don't work in the lab so much now, but I do train people and oversee the ethics of our experiments. I am meeting with the Gates Foundation soon to discuss diagnostics for tropical diseases.

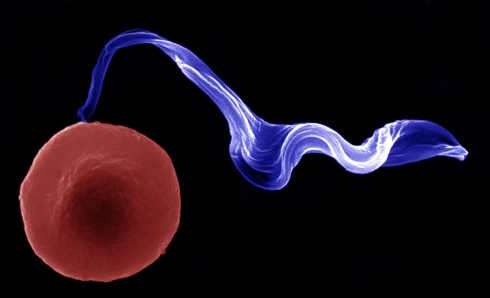

A parasitic trypanosome shown next to a human red blood

Is public health, and saving lives, what attracted you to parasitology?

Absolutely. It's about taking the technology we have here in the West and making it cost effective and simple enough to use in an endemic setting.

How did you get to where you are now?

My PhD was developing molecular tests to differentiate between types of trypanosomes. I then worked in Amsterdam at the Royal Tropical Institute developing and evaluating diagnostics for diseases such as leishmaniasis. My current role is a joint appointment between the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine (LSTM) and Warwick University.

Have you encountered lots of other strange tropical parasitic diseases while working at the LSTM?

There have been a few programmes that showed some of the highlights of LSTM, the really weird stuff. There are some fabulous parasites out there, with great examples of the weird and wonderful in nature. We have the Well-Travelled Clinic where people can come in and get their vaccinations before they go off on holiday. If they come back and they are feeling unwell, they can give us some samples, normally revealing some nasty intestinal infection.

What do you think will be important for the field in the future?

There are 17 neglected tropical diseases specified by the World Health Organization and there will be a lot of work being done to try to eliminate them.