Painting for public health

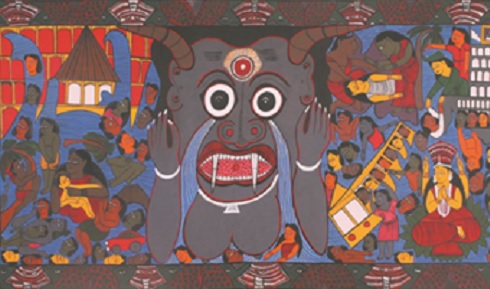

Above: Patachitra painting depicting the Asian tsunami of 2004, by Swarna Chitrakar

Information about science and health is often in written form – despite the fact that hundreds of millions of people around the world cannot read. Sreyashi Basu and Sanjib Bhakta explain how they helped raise awareness of antibiotic resistance and tuberculosis in West Bengal using the traditional storytelling folk art of the region

28th July 2021

Despite the steady rise in literacy rates over the past 50 years, there are still 773 million adults around the world who are illiterate, the majority of whom are women[1]. What many of us consider to be good examples of scientific communication, outreach work, or engagement may not actually be reaching entire communities with no access to the internet or poor rates of literacy. For some communities, especially hard-to-reach populations in low income settings, science communication should aim to transcend the use of traditional media to be more inclusive of local communication tools and forms.

The tribal art forms of India are a striking example of art that can be remodelled for scientific purposes. The vivid and colourful designs are made to embody the indigenous values of the local community through the depictions of heroes and deities from Indian mythology.

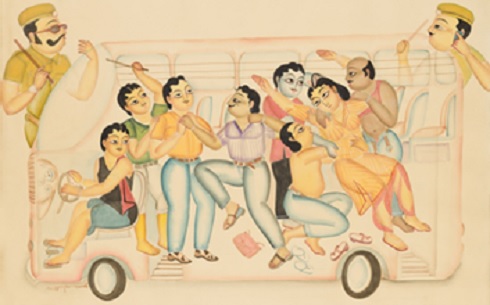

A Kalighat style Patua depicting the horrors of the infamous Nirbhaya Rape attack in New Delhi, 2012

A Kalighat style Patua depicting the horrors of the infamous Nirbhaya Rape attack in New Delhi, 2012The paintings act as a vehicle of communication within the community – driving insight about the distinctive cultural practices of the village that bring a sort of spiritual meaning to daily life. Though most artists hold strong religious values and remain isolated in their native villages, many have broken away from producing mythological themes, updating the tradition to observe and draw perspectives on urban living and the modern world. These distinctive and aesthetic forms and traditions are increasingly used to bring contemporary events and socio-political issues to life.

Some examples of famous folk paintings of India are the ‘Madhu Bani’ paintings of Bihar, ‘Warli’ folk of Maharashtra, the ‘Nirmal’ paintings of Andhra Pradesh, and Bengal’s ‘Patachitra’. Patachitra (also known as ‘Patua’), is a folk art native to West Bengal, and one of the oldest notable forms of ethnographic art to juxtapose mythological figures and contemporary articles in one frame, used to emphasize the global implications of current major events. Images are painted onto a scroll with organic dyes, scrap materials and crushed plant colours, and every piece is associated with a song, known as patua sangeet, which is sung while the scrolls are unfurled.

We wondered: could we do Patachitra focused on scientific research? Can we use this art to cultivate a safe atmosphere to ignite curiosity and discuss a scientific issue?

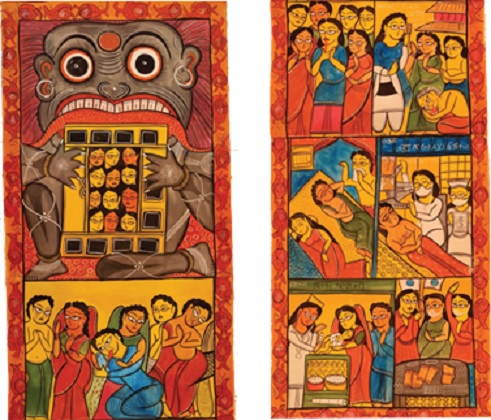

The Patachitra painting made about TB as part of the Joi Hok! project, by Swarna Chitrakar

The Patachitra painting made about TB as part of the Joi Hok! project, by Swarna ChitrakarA deadly disease

Tuberculosis (TB) is one of the leading causes of death from a single infectious agent (above HIV/AIDS). In India alone, more than 2 million people contract the disease annually, the highest incidence of TB in the world. Caused by the bacterium Mycobacterium tuberculosis, TB primarily infects the lungs, and is transmitted as aerosol droplets when an untreated patient coughs or sneezes. The emergence of multidrug resistant strains of TB (MDR-TB) remains the major barrier to TB eradication due to a lack of strategic TB control programs [2].

As with any other communicable disease, controlling TB spread is dependent on many factors. Socioeconomic and behavioural factors like lack of access to healthcare, lack of education, low literacy, malnutrition, overcrowded living, increased smoking rates, alcoholism, stigma and discrimination – all influence the spread of TB within the community, which hence makes it less surprising that TB flourishes among the poor [2].

These concerns ultimately led to the collaborative awareness campaign “Joi Hok!”, which translates as ‘Let victory be yours’ and focuses on the global fight against TB. We brainstormed ways to introduce these key concepts through Patachitra and other folk-art activities to underprivileged children in the West Bengal city of Kolkata.

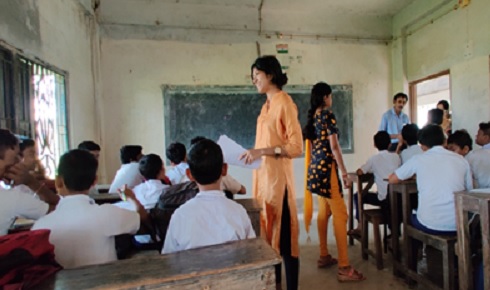

A workshop at Piyali Learning Centre (PACE Universal)

A workshop at Piyali Learning Centre (PACE Universal)Joi Hok uses the power of Patachitra art to explore the science of TB and explore the misunderstandings and stigma of having it – which have been show to delay people seeking care and reduce anti-tuberculosis treatment adherence, consequently driving the emergence of drug resistant strains in the community. It also aimed to disseminate fundamental knowledge about TB, dispel common misconceptions and explain the threat of drug resistance.

A traditional Patachitra scroll on TB was commissioned (see image above) to be presented around schools during the workshops, along with a song specially commissioned for the project[3]. As the large scroll painting is unfurled to the children, different aspects of the science of TB are revealed: common risk factors, symptoms, diagnostic methods, preventative measures. In the workshops, children were invited to participate with instruments and lyric sheets were distributed to encourage them to sing along as the Patachitra scroll on TB was presented.

Children were also asked to try sketching Patachitra comic strips on paper themselves to reflect on what they learnt about TB during the sessions and highlight some of the key messages they thought were important to take back to the community – for example using a handkerchief or going to the clinic for diagnosis without delay.

A workshop at Abhay Charan Vidyamandir School

A workshop at Abhay Charan Vidyamandir SchoolThe second folk art tool used was ‘putul naach’[3]; a traditional string puppet show hailing from Ranaghat, a small city in West Bengal. This artform is a very common method of mass education and visual storytelling used across many villages of Bengal. The puppet show narrated the story of a young man who contracted TB and faced discrimination from his family and friends. Through this and an interactive quiz after, students’ attitudes towards people with the disease were interrogated, paving the way for an open dialogue to form between educators and the students. This provided considerable insight into the issue of stigma; with students proactively sharing personal narratives in relation to how they perceived diseased family members or experienced discrimination first-hand.

The impact of this entire project was both quantitatively and qualitatively evaluated through the provision of pre and post workshop questionnaires which addressed many of the key themes introduced in the program through multiple choice and short answer questions. Collating the data from over 50 workshops, an overall improvement in knowledge among students regarding the various aspects of TB was recorded following the awareness session. This was reflected notably through questions addressing diagnosis, multi-drug resistant MDR-TB, duration of treatment, risk factors and BCG vaccination were understanding scores improved by 41.7%, 52.8%, 48% ,67.21% and 14.37% respectively.

This project has been the proud recipient of two prestigious awards; The Birkbeck public engagement award[4] and the Microbiology Society’s outreach award[5]. Additionally, the outcome of this project is presented via an invited talk on this initiative for the Society of Applied Microbiology’s Micro-talk series[6].

If you would like to learn more in regards to Joi Hok, you can visit the official webpage or find more information on Instagram, Youtube or Facebook.

While it is true that online platforms have better equipped us to engage the public on a variety of important global issues like vaccination, climate change, GMOs and evolution – this medium may not always be the correct path to take for certain audiences and their sociocultural context. Today’s youth are unbiased, receptive, and extremely creative. They have the potential to bring about the desired change in the community that we need. The use of art for advocating science is becoming increasingly popular in today’s landscape of science communication – and this medium could really have the potential to drive social change, only if we, as scientists and health experts recognize its true potential in a global setting.

Sreyashi Basu is an MSc Public Health Student at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, London

Sanjib Bhakta FRSB is professor of molecular microbiology and biochemistry within the Department of Biological Sciences, Birkbeck, where he leads the mycobacteria Research Laboratory at the Institute of Structural and Molecular Biology

1. UNESCO figures on literacy

2. WHO fact-sheet on tuberculosis

3. Joi Hok resources

4. Birbeck University research blog: public engagement awards

5. The Microbiology Society, news: 2020 outreach prize

6. Society for Applied Microbiology: A novel approach toward raising awareness of tuberculosis amongst children in a low income setting