The wildlife of Chernobyl: 30 years without man

In the 30 years since the disaster at Chernobyl, wildlife in the highly radioactive 'Exclusion Zone' has thrived. Mike Wood and Nick Beresford report from a nature reserve like no other

The Biologist 63(2) p16-19

The world's worst nuclear accident occurred 30 years ago this April. In the early hours of Saturday 26th April 1986, an explosion and subsequent fire at Reactor 4 of the Chernobyl nuclear power plant (NPP) released large quantities of radioactive material into the environment. The plume of radioactive contaminants spread over much of Europe. The highest levels of contamination were in the area surrounding the Chernobyl NPP, a region spanning the Ukraine-Belarus border now known as the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone.

To many, the notion of a radioactive zone from which 116,000 people were evacuated evokes images of a post-apocalyptic world. However, Chernobyl is not a scene of devastation. In fact, it turns out that when humans are removed from an area – even one contaminated with radiation – nature has a remarkable ability to reclaim that space.

Covering a land area equivalent to Northumbria, the Chernobyl exclusion zone provides a diversity of habitats for wildlife, including pine forests, deciduous forests, grasslands, wetlands, rivers, lakes and abandoned towns. But what types of animals live in the shadow of Chernobyl and does the level of radiation in an area influence the animals that are present?

To help answer these questions, we have been studying the wildlife of the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone using motion-activated cameras to survey medium to large animals (primarily mammals) in different parts of the zone. We focused on three 80km² study locations, approximating to comparatively low, medium and high-contamination areas. Over the 12-month study, each 80km² area had at least 84 random camera placements covering the diversity of habitats present. This resulted in more than 90,000 camera days and upwards of 155,000 images.

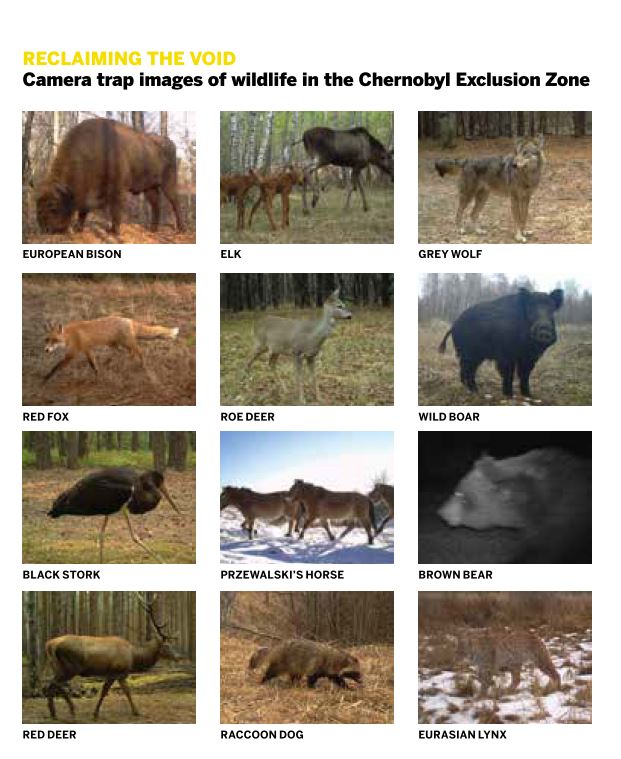

Our cameras captured pictures of a fascinating range of Europe's medium to large mammals, including European badger (Meles meles), Eurasian beaver (Castor fiber), elk (Alces alces), Eurasian lynx (Lynx lynx), grey wolf (Canis lupus), raccoon dog (Nyctereutes procyonoides), red deer (Cervus elaphus), red fox (Vulpes vulpes), roe deer (Capreolus capreolus) and wild boar (Sus scrofa). These have been accompanied by some interesting firsts, including some of the first photographic evidence of brown bear (Ursus arctos) returning to the zone and the first evidence of European bison (Bison bonasus) in the Ukrainian side of the zone.

There are also many photographs of endangered Przewalski's horses (Equus przewalskii). Approximately 30 of these horses were released into the Ukrainian side of the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone during the late 1990s. Our cameras have captured images of Przewalski's horses with a brand identifying them as some of the original horses that were released, as well as images of unbranded adult horses, juveniles and foals, suggesting that the population is breeding successfully within the zone.

Mammals pictured within the highly radioactive Chernobyl Exclusion Zone include brown bears and the Eurasian lynx

Mammals pictured within the highly radioactive Chernobyl Exclusion Zone include brown bears and the Eurasian lynxWe want people to see the reality for themselves. For that reason, we have developed cutting-edge virtual reality and immersive projection chamber experiences (see Exploring Chernobyl, below).

30th Anniversary reflections

Chernobyl clearly took a significant human toll, with the large-scale permanent displacement of people from the Chernobyl region. Thirty years on, we find ourselves reflecting on this, while simultaneously marvelling at the fascinating diversity of wildlife that has reclaimed the area.

The camera-based study provides data on the distribution and relative abundance of wildlife in the zone, but it does not allow us to establish if radiation is affecting individual animals – further research is required to evaluate this. The zone today could be viewed as a living laboratory in which we can study the effects of radiation on wildlife and learn more about important ecological research areas, such as the process of rewilding in abandoned spaces.

We hope the international scientific community will continue to capitalise on these research opportunities, ensuring that there is at least some 'benefit' from the world's worst nuclear disaster.

Exploring Chernobyl from a seat in Salford

Using the latest virtual reality (VR) technology, researchers from the University of Salford have created a safe way for members of the public to explore the blossoming woodland of the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone.

As part of the university's annual science festival, researchers pieced together video footage, photographs and camera-trap images to create a virtual world for visitors to explore.

Strapping on a high-tech Oculus Rift VR headset, visitors look around to navigate to various points in the infamous area – from the main reactor site and surrounding abandoned villages to a fairground that never opened. At each scene, visitors can explore the wilderness above, below, to the left and right, and behind them. Headphones play soundscapes recorded at each scene, hissing with wildlife and the sound of wind in the grass.

The second part of the installation is a video montage of camera trap footage from Chernobyl projected onto the surrounding four walls. Dr Wood explains how and why biodiversity is blooming in the area as elk, lynx, boar and even an elusive brown bear appear out of the woods. It's a stunning way of taking people into the heart of this dangerous place.

The radiation at Chernobyl will keep humans away for thousands of years. And that, despite the radiation levels, seems to be quite enough to enable the wildlife here to thrive.

The exhibition will be running at Manchester's Museum of Science & Industry on 23rd and 24th April 2016.

Dr Mike Wood is reader in applied ecology at the University of Salford, UK. He leads the TREE project camera-based research on the wildlife of the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone.

Professor Nick Beresford CBiol MRSB is environmental contaminants group leader at NERC-CEH, UK, and honorary professor at the University of Salford. He has spent more than 25 years studying the environmental impact of the Chernobyl disaster.

The camera study discussed here is part of the TREE project, a five-year programme of research in the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone that is funded by the Natural Environment Research Council, the Environment Agency and Radioactive Waste Management Ltd

For further details on our work, visit the TREE project website (www.ceh.ac.uk/TREE) or follow us on Twitter: @DrMikeWood & @radioecology

The authors gratefully acknowledge the support of their Ukrainian research collaborator, Dr Sergey Gashchak, and Professor Andy Miah, Simon Campion and Dr Michal Cieciura for their work on the 'Alienated Life' exhibition

Further reading/ References

1) Beresford N. A. & Copplestone, D. Effects of ionizing radiation on wildlife: What knowledge have we gained between the Chernobyl and Fukushima accidents? Integrated Environmental Assessment and Management 7(3), 371–373 (2011).

2) Deryabina T. G., et al. Long-term census data reveal abundant wildlife populations at Chernobyl. Current Biology 25(19), R824–R826 (2015).